Less than .5 percent of the US population serves in the military, largely as a result of the 1973 decision that ended the military draft and transitioned the US Armed Forces to an all-volunteer force. As we learned in chapter 2, military culture fits the standard definition of a culture. It has a unique vocabulary, its own rituals and rites as well as dress codes and behavioral standards.

The civilian-military chasm can be one of the major barriers to a veteran’s successful reintegration into their communities. Veterans often feel stereotyped by film portrayals and news reports about gun-wielding violent veterans with PTSD wreaking havoc on their families or their communities. These false assumptions that non-veterans may harbor can create stigma among veterans, impact their care-seeking behavior, and influence how they perceive a non-veteran provider will respond to their experiences and needs.

We know as providers that traumatic events and adverse mental health outcomes are not confined to the military community. However, it is important for you to understand that although the case definitions of mental and behavioral health conditions may be the same, the context (both cultural and experiential) are quite different and can be more complex among veterans.

WHAT YOU SAY AND HOW YOU SAY IT MATTERS

Like many unique populations, vocabulary and language use play a key role in effective engagement with veterans. Here are a few key tips for communicating with veterans:

- Instead of asking if a new patient is a veteran, ask if they have ever been in the military. Not all veterans self-identify. Asking if they have ever been in the military is asking about a fact of their life. Asking if they are a veteran is a question of identity.

- Although you may be tempted to use the more clinical term “disorder” when discussing a diagnosis, that word carries a lot of stigma. It is better to use the word “condition” when discussing with or about veterans. For veterans seeking mental healthcare, a mental health diagnosis is fraught with perceived stigma coming from a culture that emphasizes strength and resilience. In addition, many service members fear a mental health diagnosis or treatment may jeopardize their chances for professional advancement.

- Although saying “thank you for your service” is a well-intended phrase, it is best not to say this to a veteran because it assumes they feel their service was worthy of praise. Unfortunately, not all veterans feel positive about their time in the military. In addition, it does not really start a conversation, but is a way to conclude a conversation.

- Never assume you know about your patient’s military experiences based on news reports or the films you’ve seen, relatives’ or friends’ experiences, or even your own if you are also a veteran. Your conversation will be richer and more informative if you ask open-ended, specific, and factual questions about their time in the military. Using words such as “describe” or phrases such as “tell me about” can yield rich informative narratives.

For additional effective communication suggestions, see the Approach to Care chapter.

THE IMPORTANCE OF KNOWING WHEN A VETERAN SERVED

Not only is it important to identify if a client or patient is a veteran, but you will also want to know their era of service. Knowing when a patient served in the military is important because veterans’ experiences and risks vary.

Post-9/11: Over the course of time, weapons and logistics of war have changed significantly. During earlier wars, the battlelines were clear and linear. But as time has passed, guerilla warfare and insurgencies have transformed armed conflict to a 360-degree battlefield with no clear lines of engagement. There is no front and no rear. The weapons of war were previously primarily confined to firearms and directed explosive devices such as mortars or grenades. Now, we see more widespread use of Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) which are harder to detect and can be even more lethal and disabling. Consequently, trauma can come from any direction and any thing.

Post-9/11 veterans fought in an environment that was far more unpredictable than previous era veterans, which is why you might see more hyper-vigilance in your clients who are post-9/11 veterans than veterans of earlier eras.

Not only has warfare itself changed, but there are several other key differences between US military operations during current wars and previous wars that have been linked to mental health outcomes, most notably:

- Current era veterans likely had multiple deployments, which means risk of multiple trauma exposures.

- While women veterans have long served in combat, they were never given recognition or formal combat roles until recently. This has led to both increased rates of mental health conditions and diagnoses among women veterans as they are being recognized for combat service.

- As previously mentioned, an all-volunteer military has decreased community engagement with returning service members and increased alienation among veterans.

Importantly, post-9/11 veterans served in an all-volunteer military with multiple deployments and a reliance on a smaller force. Far fewer Americans had a personal connection to the wars and their consequences, leaving the public disengaged. But while post-9/11 veterans fought in a war that some Americans opposed, the public’s opposition focused on those who authorized it and not on those who fought in it. The sea of goodwill extended quickly, and government and philanthropic support followed. However, the yellow ribbons have largely been put away, and many current generation veterans feel the public has forgotten about their continuing needs.

Gulf War: Gulf War veterans fought in an historically short war. They were deployed to the Persian Gulf, weathering windstorms while waiting to actually engage in combat, and then fought in a war that lasted only a few weeks. Despite the relatively short length of time they were deployed, many of those who had served in the conflict later complained of a combination of neurological and other physical health symptoms that were initially dismissed as psychosomatic because they did not align with any previously observed combination of symptoms. (Please see the Physical Health chapter for more details about Gulf War illnesses).

Research also suggests that Gulf War illnesses’ symptoms co-occur with mental health conditions, particularly PTSD. Gulf War veterans have a history of providers not believing them when they describe their health symptoms. Imagine how that experience with healthcare providers might influence their trust and interactions to this day.

Post-Vietnam Era: The most overlooked veteran cohort may be those who served when the US was not actively involved in a war—specifically post-Vietnam era veterans. The fact that they did not serve in a war does not mean they were not at risk for mental and behavioral health outcomes. Keep in mind that post-Vietnam veterans share a number of the non-combat risks for mental health conditions as those who served during a war era. This veteran cohort has been found to have higher rates of homelessness and substance use disorders than other veterans.

Vietnam: A veteran who served during the Vietnam era had other experiences that differed from those of their counterparts who served during more recent war eras and these differences contributed to their level of community disconnect.

Vietnam veterans were part of a draft and served at a time when the public was more engaged with the war itself. The draft meant that more American families were personally impacted by the conflict, and for the first time, families were able to see the horrors of war on their televisions in real-time. This and other factors led to an unpopular war, and Vietnam veterans and were not greeted with fanfare or provided necessary support. Decades of neglect followed, a legacy that still pervades among the Vietnam veterans still in need of mental healthcare and housing to this day.

BARRIERS TO CARE

A number of factors pose the greatest barriers to veterans seeking mental health treatment or reporting symptoms, including:

- Stigma, or personal shame, about having a mental health problem.

- Long wait times at VA facilities.

- Fear that they will be regarded as weak.

- Lack of awareness about mental health and the available treatments.

- Long travel distances to access treatment.

- Lack of confidence or trust in the VA’s mental health treatment or clinicians.

- Demographic barriers and perceived discrimination.

Post-9/11 service members may also avoid reporting mental health symptoms during post-deployment screenings because of concerns that doing so may delay their release from military service or jeopardize future career success. These barriers as well as lack of and disparities in access to mental healthcare may be a leading factor in the high suicide rates in veterans who have PTSD or depression.

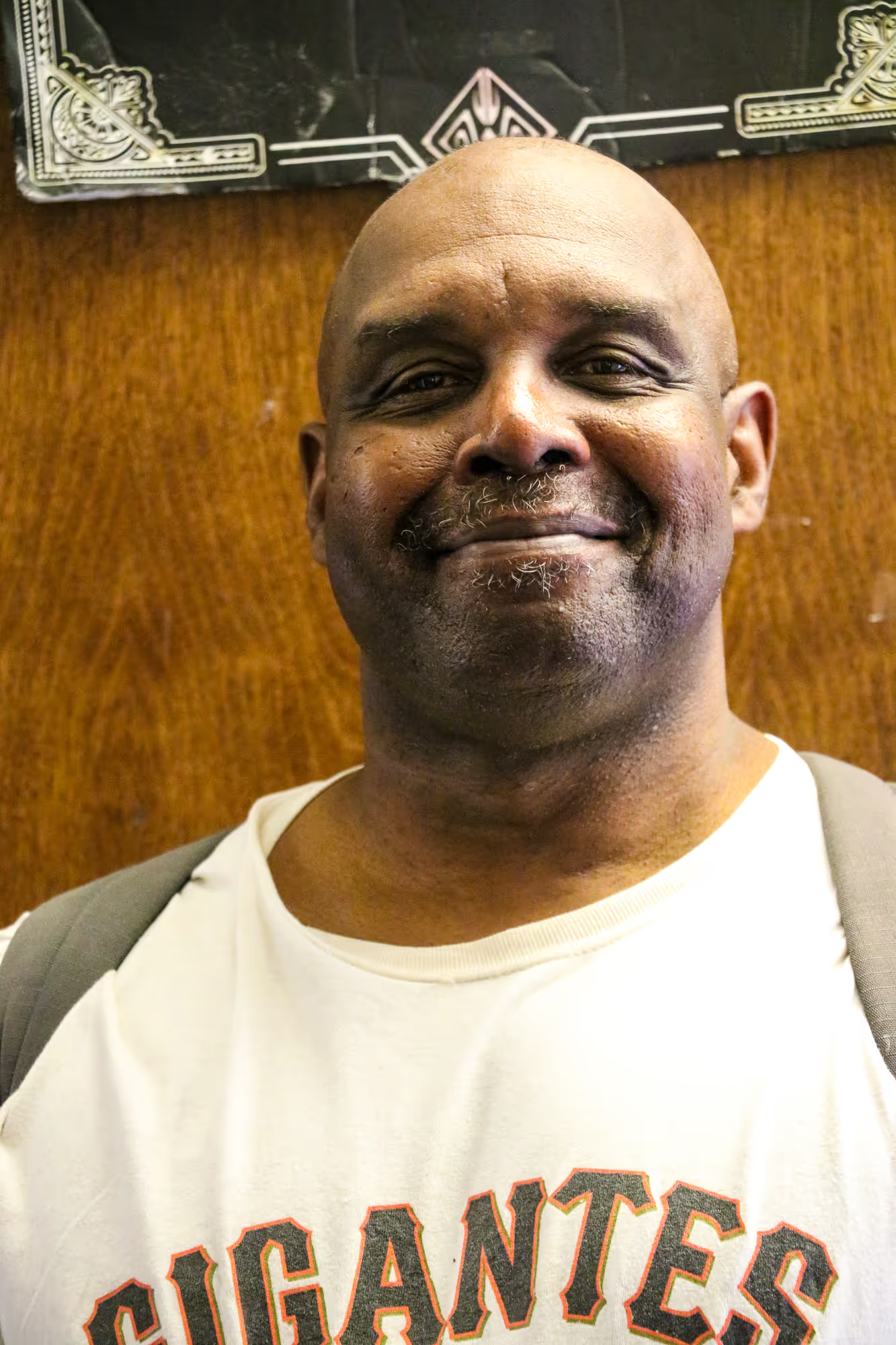

Watch Shannon, Navy Veteran, retell how his father, also a veteran, taught Shannon that veterans may store away memories of trauma. (2:13)